I came across this recent paper published in Nature Communications on the Cambaytheres, a group of mammals I have to confess I had not heard of before, but the article made me think about horses and insurgents.

In the paper, Kenneth Rose and his co-authors claim that 50 million-year-old fossils found in an old mine in Gujarat, India tell us that horses, rhinos, and tapirs, or the Perissodactyla, originated in India. What’s interesting is that 50 million years ago, India was an island, adrift at sea, heading for a horrific, slow crash with Eurasia.

India adrift. Cruising from the south after her split up with Africa and Australia and her abandonment of Madagascar, she crashed into Eurasia. The mountains to the north are the crumpled regions of the crash. Part of her western region is known as Pakistan.

It’s hard to fathom – but India began as a massive chunk of land squeezed between Africa and Australia in the Southern Hemisphere a half a billion years ago. She broke free and fled across the sea, leaving Madagascar behind but taking Sri Lanka with her until she crashed violently into Asia – the Himalayan mountain range is like massive, rumpled bumper of the crash.

When I close my eyes, I see India cruising at top speed across the ocean, breaking waves, leaving a huge wake, but, of course, the actual trip took a couple hundred million years, so I doubt any of the creatures on board noticed or felt even mildly seasick.

What Rose and his colleagues tell us is that some of the creatures on board were the evolutionary ancestors of the Perissodactyla. The fossils they examined are bones of Cambaytherium species, mammals from the Indo-Pakistan region dating back to the Eocene, some 56 to 33 million years ago. Since the Cambaytherium share a common ancestor with the Perissodactyla, and India was an island at the time, the evolutionary roots of horses, rhinos, and tapirs must be Indian.

It’s hard now, when looking at the horses in Central Park or the police horses in Times Square, to not want to go up and ask them what it’s like to be of Indian ancestry – I always felt a kinship with them, as I do with all creatures, but now I feel a little closer. My bacterial cousins go back 3.5 billion years, but my horse cousins go back a mere 50 million years – that practically makes them siblings rather than cousins.

I’ve been to Gujarat. My student, Meha Jain, worked in Gujarat, so I went to see her doing her dissertation work. I had a fantastic time during my visit. I didn’t have time to go see the last remaining population of the endangered Asiatic Lion and the endangered Asiatic Wild Ass that reside in reserves in Gujarat. When I travel, I try to visit nature, but there wasn’t time and the reserves were far away. The rural farmscape, however, though devoid of natural habitat, had a beauty of its own.

Like many, of course, I knew Gujarat for the 2002 massacre of hundreds of Muslims and the displacement of thousands more. A center for Hindu nationalism, a violent history, and the complicity of its Governor, Narendra Modi, in the violence, seemed contrary to its warm and gracious people and its intricate culture. In spite of Modi’s dubious past, he was immensely popular in Gujarat, his portrait was everywhere, and today, he is India’s Prime Minister. When he visited here in late September, he was greeted as if he were some sort of hero – at Madison Square Garden, an audience of 19,000 cheered.

When I think of Gujarat, I think of India and about its extraordinary geological and biological history that generated amazing natural wealth – some of the most unique and diverse flora and fauna in the world are found in India. When we, by which I mean our species, arrived in India, out of Africa and on our way to South East Asia and eventually to Australia and New Zealand, many of us must have stayed in places that must have seemed like the fictional Shangri La.

Out of Africa and into India happened only 50 to 70 thousand years ago, yet, in that short time, and particularly in the last 100 years of colonialism and postcolonialism, we have spent down the natural wealth of the region. With the spending down of that natural capital, as economists call it, to make built capital, another economics term, we now have farms that barely support their people and cities that lack the resources to provide the kind of infrastructure necessary to make urban environments work well for many. Some 270 million people live in poverty in India – how did that happen?

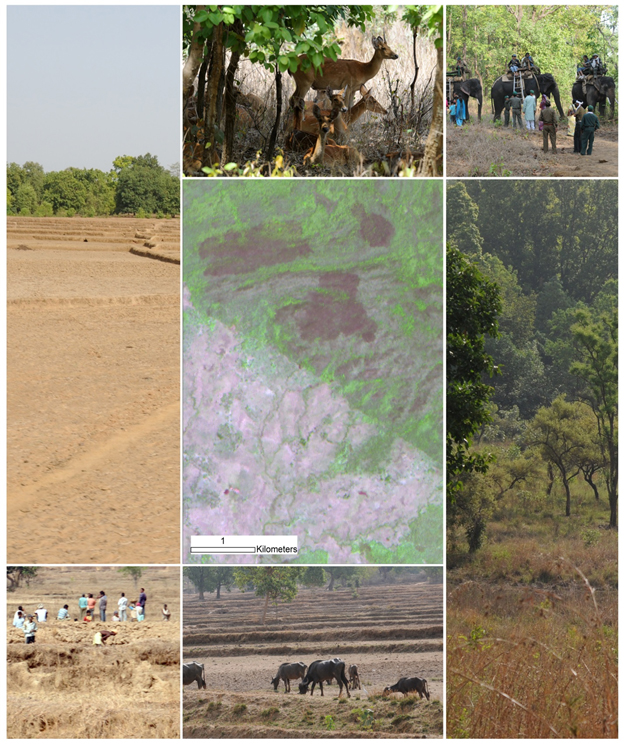

Then (50 thousand years ago) and now. The center shows a satellite image of Khana National Park (green area above the diagonal which is the park boundary) vs. agricultural transformation (whitish areas left of the boundary). Pictures on top and left are from the park, while pictures on the bottom and right are of the surrounding landscape. I took all these pictures on a single day in August, 2009 and the figure was published in an article.

Naeem, S. and R. DeFries. 2009. La conservation des espèces, clé d’une adaptation climatique durable., Institut du développement durable et des relations internationals. Sciences Po., Paris, France.

I’m not a political scientist and have no particular authority on social or humanist matters, but it seems to me that the end result of the loss of nature’s capital is a rise in insurgency. In the general region, Sunni insurgents attack Iran, the Jaish-e-Mohammed, Harakat ul-Mujahidin and Lashkar-e Tayyiba fighters fight with the Pakistani government, the Taliban attack Afghanis, Sikh insurgents in Punjab attack their fellow citizens as do Naxalite Maoists in Eastern India. In the grand scheme of things, these violent conflicts are small compared to the hundreds of millions who reside peacefully in the region, but that is cold comfort to the innocent killed or injured in the struggles. Worse, insurgency is a source of omnipresent fear and often an obstacle to tackling other issues, such as poverty, income inequality, and environmental degradation – the very things that breed insurgency. In the US, for example, we invest less and less in the environment, but out of fear and distraction, we have spent 2 – 5 trillion dollars on fighting insurgents since 9/11.

I know my thinking is often pretty circuitous, to say the least, but that’s what the paper by Rose and his colleagues does for me. Now, when I see horses, I think of India and its extraordinary biogeographical history and how, in the geological blink of an eye, we transformed the very places within which we and biological diversity prospered, to landscapes that, in the absence of any ecologically sensible stewardship, lead to poverty, inequality, and the autocatalysis of insurgency.