I’ve never been to Pakistan, though my father, who was born before the country’s birth, saw it as his homeland and after raising a family here in the US, returned to pass away on its soil. Americans (all kinds) think me Pakistani or Indian. It’s a strange American custom – to consider anyone outside their sense of the “American ordinary” to be non-American.

“Where are you from?”

“New York.”

“No, I mean, where were you born?”

“San Francisco.”

“No, I mean, where are you from?”

Sadly, I’m just an American, though I’m tempted to say something exotic, like “The Seychelles,” in a thick French accent. I’ve never been there, but then, I‘ve never been to Pakistan either.

Oddly, Pakistanis seem to think me Pakistani too, as though I’m a branch off an ancient tree of humanity that’ s rooted in Pakistan, though the country was only created in 1947. It’s interesting to me how often I am approached to be brought into the fold of something I really do not know – no matter that I was born here, have never been to the country and don’t speak Urdu.

Years ago, I realized that the only sensible answer to questions about one’s identity and allegiance is simply “I am from the Tree of Life, a citizen of the Biosphere, kin to 8.7 million species; my trade is biogeochemistry, the universal trade of all organisms.”

That sounds nerdish, Lovelockian, or Earth Motherish, however. Safer to say, “The Seychelles.”

By dodging the question of “where were you born?” I’m really trying to avoid tribalism, something I feel is an unfortunate and destructive trait of mankind. To ask the question “where were you born?” is to reveal subscription to tribalism – that we belong to some kin, clique, or clan, no matter that we are all one species. In fact, our species is only a couple hundred thousand years old – still a twiglet, in evolutionary terms. A miniscule twiglet of a 3.5 billion year old tree made up of millions and millions of branches.

On the spectrum of finding human tribalism wondrous to finding it abhorrent, I cannot find where best to stand, so I avoid the issue. Some folks are obsessed with their “roots.” But they tend to stop once they identify with some monarch or emperor. Logically, if they kept going, they would wind up with Mitochondrial Eve, the mother of us all, who was born of non-Homo sapiens sapiens primates in East Africa some 200 thousand years ago. But I don’t understand why one would stop there? Personally, I like going back to the cyanobacteria who gave us oxygen, but I’d be happy to go back to the first cell, maybe even the first microscopic lipid bubble that contained the RNA, DNA, proteins, and carbohydrates necessary to replicate itself.

What’s wrong with tribalism, seeing oneself as a branch or twig or twiglet of humanity rather than as just another member of the living world?

Tribalism is the engine of human disparity, inequality, and inequity, and ultimately why the living world is facing an uncertain future.

My Facebook friends from Pakistan do not understand why the world seems to have already forgotten the slaughter of 135 children in Pakistan by deranged people motivated to murder by a pathological form of tribal exceptionalism, by which I mean seeing one’s tribe as exceptional, superior to others, to the point that one can mistreat or even kill those of other tribes. In this case, the tribal exceptionalism is Taliban supremacy.The Pakistani Taliban, self-confessed perpetrators of the slaughter, having previously bombed or burned more than a thousand schools, vow to do more. It is beyond comprehension, and beyond humanity. How could it have happened?

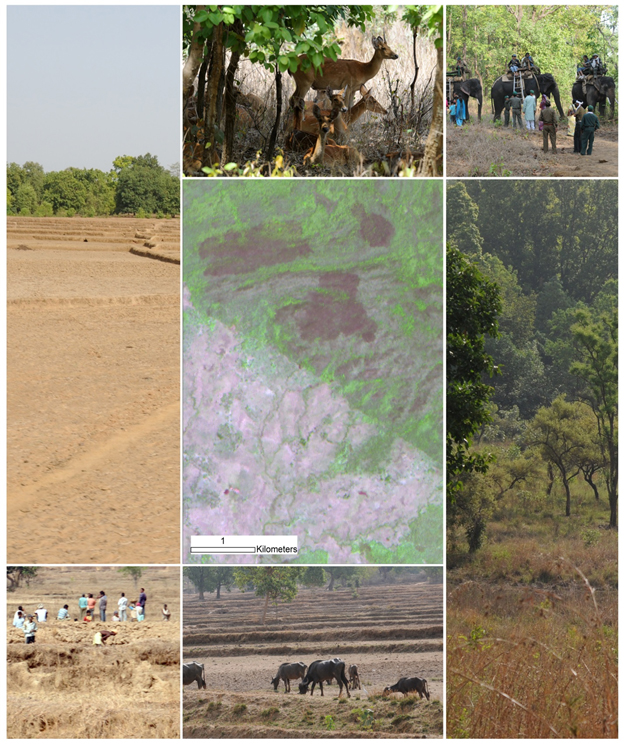

In writing on the wanton killing of endangered bustards by a Saudi Prince hunting in Pakistan, I was reminded of how complex Pakistan is as a small country bordered by the much larger India, Iran, Afghanistan, and the complex and troubled Kashhmir and Jammu lands in the north. It is embedded in a turbulent mix of cultures, ideologies, politics, history, economics, and now, environmental change. Amidst such complexity, the unthinkable can happen. With so many endogenous and exogenous forces at play, inevitably something terrible will happen in spite of Pakistan’s best efforts. In spite of the turmoil and complexity surrounding Pakistan, it is also home to the first woman leader of an Islamic country (Benazir Bhutto) and home to this year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner (Malala Yousafzai, the girl who survived being shot by the Taliban for the audacity of going to school).

The more complex and turbulent the environment we live in, the more exogenous forces are likely to get the upper hand.

Slaughters, mass killings, genocide, the outcome of complex and turbulent environments, are all too common in our species, but we are outraged by the murder of children – no matter the tribe.

When we mourn the death of children at the hands of men, we mourn the loss of children of the Tree of Life.

And yet, in spite of outrage, in 2012, around the world, 10 million children were forced into prostitution. More than 168 million children were exploited as laborers, often under terrible and hazardous conditions. 5 million died from hunger and malnutrition, and the gruesome numbers go on.

In the US, 1,640 children died from abuse and neglect, 88% under the age of 7. Between 2005 and 2009, 1,579 children were murdered here. And though hunger and poverty have been rising at a steady clip (1 family out of 10 struggles to put food on the table in our country), in the most recent US budget, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, designed in part to insure child welfare, was slashed by 8.6 billion dollars.

Of the 150 gun laws proposed in the US since the Sandy Hook massacre of 20 children by a deranged gunman (note frequent use of the word “deranged”), only 109 laws have been enacted, but the vast majority (70) of them loosen gun restrictions. We want our guns allegedly to protect our family, kin, clan, and tribe (oh yes, and to hunt).

Today in our country it is easier than ever before to kill children with guns.

There’s no overcoming tribalism, and my friends and colleagues think it wondrous (they term it “cultural diversity,” but that is the manifestation of tribalism), the suffering of children being an unfortunate outcome that needs to be redressed. I love cultural diversity, one of the reasons I love New York City as a home, but if cultural diversity can only be generated by tribalism, then it isn’t worth it. I would rather see people in love with one another and their children than in love with their tribe.

Globally, most of the trends in child welfare are in the right direction – declining child labor, increasing child health, fewer girls killed or genitally mutilated, and in our country, greater awareness and lower tolerance for the abuse and slaughter of children. But increasing economic disparity and environmental disequilibrium make sustaining positive trends difficult. This is why the greatest champions of the welfare of children are those who work tirelessly to build broad environmental sustainability and insure that the world remains a robust home for all of us, especially children, who are the first to suffer when food, water, and energy becomes scarce, as climate changes, diseases emerge, and conflict arises.